Mustafah Abdulaziz, Photographer

Mustafah Abdulaziz is an American documentary photographer living in Berlin. He started a 15-year-long project called Water in 2011—a photographic documentation of human beings and their interaction with water—and intends on shooting this project until 2026.

He has been named PDN’s 30 Emerging Photographers to Watch and Water has received support from the United Nations, WaterAid, VSCO, and Google. In 2018, he became a fellow of the 53rd Annual Fellowship of The Alicia Patterson Foundation.

Mustafah shares photo books that inspire his work, thoughts on the current state of the industry, and a photographic memory that changed his life.

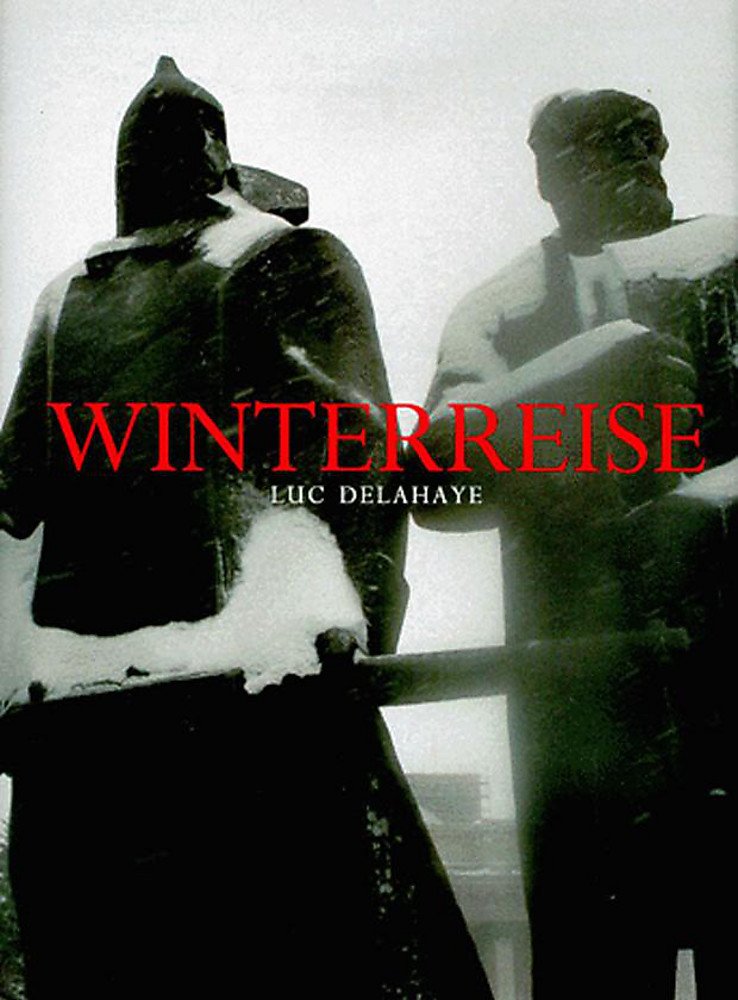

Winterreise,

by Luc Delahaye

“Nearly devoid of all text, printed full bleed, claustrophobic and unsettling. This is as much a portrait of Russia’s underclass as it is one man’s wanderings. The sequences churn along like a locomotive: arrays of oppressive yellows, faded wallpapers and bleak landscapes that become intimate stages for scenes of great humanity that drift between loneliness and despair. This book heavily influenced my desire to merge the personal journey with the ceaseless sensation of seeing the intimate lives of others.”

Petrochemical America,

by Richard Misrach and Kate Orff

“The book’s combination of photographs, in-depth research and ‘speculative drawings’ by landscape architect Kate Orff make for a fascinating portrayal of the layered and deep-rooted way in which Americans have plundered their environment for resources and the devastating legacies these behaviors have left behind. This book came out around the time I began Water and was immediately a benchmark I aspire to. The story of Man and Nature is, I believe, one of the most pertinent of our contemporary challenges.”

In the American West,

by Richard Avedon

“The significance of this book on my decision to become a photographer cannot be understated. It’s one of my earliest memories of seeing photography. The sensation of having a part of my mind unlocked, or perhaps the embers of curiosity stoked, impacted me greatly. I’m quite sentimental about this book, won’t own a copy myself and don’t look at it when it’s around. There are some things in this world that may be magic. This book gets pretty damn close.”

Self Portraits with Cows Going Home,

by Sylvia Plachy

“When Plachy was thirteen-years-old in 1956, her family fled the Hungarian Revolution for the U.S. with just a suitcase. This book, told non-linearly across color and black & white photographs, souvenirs and relics, and her writings, is a beautiful act of remembering. The book touches on the feeling of home and displacement, family history and creating new history. She goes back to Hungary across forty years, photographing places both alien and familiar brining us into the bedrooms and gardens of her memory.”

What is something in your industry that deserves more attention?

There are few that come to mind. The one that feels strongest is from Snæfellsnes Peninsula in the western reaches of Iceland. It was 2016 and I was producing a new aspect to “Water” about this stormy coast. A friend and I spent our time outdoors nearly every waking hour, exposed to the elements, buoyant and boyish. Much has been said of the Icelandic landscape. You simply need to walk in any direction for a few minutes before you see something beautiful.

In Snæfellsnes, there are these lava fields and mossy expanses, cliffs that drop from significant heights into crashing whirlpools of volcanic rock and sea. We were exploring this stretch of land for days, photographing and wandering. Always drenched or nearly numb, warming in the afternoon with possibly the best fish soup ever laid to ladle.

Memories exist in this atmosphere: wind making tears at the edge of my vision, huddling in a volcanic pit as larger and larger swells smash into the rocks close by, spraying salt water. Breathing onto my fingers so they could adjust the camera, but finding it makes no difference. My mate Robbie, smiling wide as the next wave slammed into the black rock, wearing the same look of abandon and pure presence that was on my face.

This is where photography stopped being a thing I do or create or make. It was, then and now, the act of bringing me ever closer to the visceral. The real. That is the gift.

What are the main differences between living and working in both the United States and Europe as a photographer, if any? Is photography seen or treated differently between the two?

In the U.S., there is a cultural drive that is really hard for me to accept. Particularly from the inside, as I believe it somehow serves the neuroticism of this behavioral mode of constant work and social status gained from being—or appearing to be—busy and driven. This may seem like a generalization but it is my own experience. I’ve considered this perhaps too much. As a person and photographer, I do not feel at home in the States anymore. There is almost a narcissistic obsession with one’s own success. I simply wish to value different things.

I can only speak from personal experience. Living in Berlin for seven years and working across Europe has forced me to find a calmer, more reserved way of pursuing my work. It’s a bit harder for me to extrapolate how photography is seen or treated between each. For the most part, I keep to myself and don’t often interact in these spaces or even look at photography. I can only say that my experience here has propelled many transformations, some I was even quite reluctant to accept.

In essence: evolution of the self propelled by a different set of priorities provided by the openness of the place I live.

What are some habits that keep you going when working on a long term project like Water?

One habit is to remind me that this isn’t the most important thing in the world.

It may mean a lot to me but there are many other aspects of personal life that have to be cared for. This habit is born of a lesson that was particularly hard for me to learn. Remembering this helps out a lot.

Embracing failure is another habit because it requires a person to retain the willingness to understand the lessons it can impart.

Another habit is something wonderful I read once from Georgia O’Keeffe. She said, “I have already settled it for myself so flattery and criticism go down the same drain and I am quite free.”