Sasha Waters Freyer, Filmmaker

Sasha Waters Freyer is a filmmaker and serves as the Chair of the Department of Photography and Film at Virginia Commonwealth University.

In 2018, her documentary,Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable premiered at the 2018 SXSW Film Festival, where it won a Special Jury Prize. Other works include lyrical explorations of motherhood, and essay films on the cultural and political legacies of the late 20th century. From 2015-2017, she hosted a mobile art exhibition project at Bust Gallery. She is included in a survey of 139 Women Film Editors who "invented, developed fine-tuned, and revolutionized the art of film editing.”

The Animals,

by Garry Winogrand

“In my documentary, Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable, SF MoMA curator Erin O’Toole describes Winogrand’s The Animals as a book that is almost easy to dismiss because it ‘seems so casual.’ As a beginning photographer, what drew me to the book was the way Winogrand makes the wit and grace of those zoo pictures look nearly effortless, as though the unscripted dramas of human-animal interactions are readily available to anyone with a camera. They are not: it is super hard to make an inventive, original, funny and pathos-infused picture at the zoo. Winogrand’s The Animals is a lyrical, authorial vision that synthesizes detachment and sympathy, judgment and forgiveness. The images perform subtle social satire while at the same time (with some digging and context), reveal his individual psychology at the time of their production.”

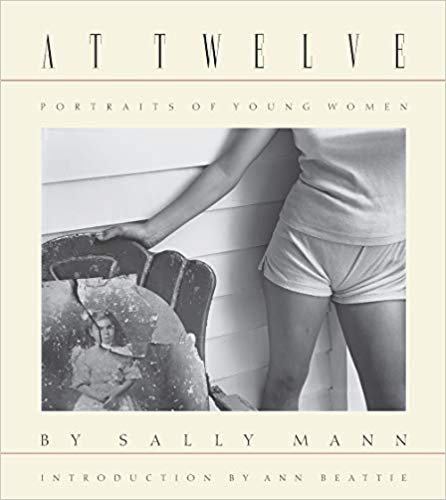

At Twelve,

by Sally Mann

“Sally Mann’s first book, At Twelve, was released in 1988 and made an immediate impression on me as a young student of photography. I was not even a decade older than the young women depicted so intimately in these lush pix, and yet that tender age already felt like a ‘paradise lost’ — which likely says more about me and my own projections, fantasies, and fears of youth. The best photographs in Mann’s At Twelve capture the irretrievable magic of that fleeting age — how within a face, a gesture, the canny viewer might glimpse the girl of four, the woman of forty and the crone at eighty, instantly and simultaneously. These are Carson McCuller’s novel of impassioned and confused adolescence, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, come to frozen life in girls we might now call ’tweens’ of the American South; painfully intimate pictures of the river of time.”

Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity,

by Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith.

“Pictures and Progress is a crucial 2012 publication that illuminates the social function of photography and its effects on racialized thinking in the late 19th and early 20th century. As we continue to grapple with adequate, appropriate and empowered representations of race and ethnicity under white supremacy, this book both analyzes the work of four early African-American photographers, and argues — in essays from a range of disciplines and perspectives — how photography was deployed as a tool in the service of racial justice in the pre- and post-Civil War eras. As a documentarian and teacher concerned with the ethics of representation, I return to this book again and again as a rich and critical resource for exploring and understanding the relationship between image and agency.”

[Symbol] : (the book currently known as ...), by Justin James Reed

“I love this beautiful, smart, far out book, titled as a symbol, for the bridge it builds between the romance of early landscape photography on the one hand, and the technological innovation of its production on the other. Its images are painstakingly etched on paper with a laser engraving machine and presented in a custom crafted glass box with the title sandblasted onto its surface. It is completely contemporary in its material exploration and its pushing of the boundaries ‘photo book-ness’. Yet at the same time feels like it could have been discovered at a distant archeological dig, possibly one rumored to house the remains of alien life forms. [symbol] is past and future, old and new, deep space and whispered mysticism and as such, is a thrilling reminder of what books can be and do.”

Sasha, you recently released the documentary “Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable”, about the life and work of photography legend Garry Winogrand. Making a film is hard work and requires long commitments. How do you choose what projects to work on?

I realize this may sound clichéd, but it's true! I feel like projects pick me, rather than the other way around … meaning, if I hit on an idea and just can't let it go, shake off my interest, I know it has a hold of my imagination and I want, even need, to spend time exploring it.

With “Winogrand” I wondered why there hadn't ever been a documentary about the man and his work, and I wanted to see that film. It didn't have to be me that made it, but since I couldn't let it go, and since no one else was working on developing it, it ended up being me.

Another way of explaining is to say that I make films I'd like to see in the world.

After a big project like like that, how do you recharge and get ready for the next project?

I love to read and listen to books — fiction, non-fiction, criticism, etc. Not as official "research" but to energize my mind and imagination around ideas and stories.

I am a lover of books, mostly fiction, but also poetry too. Inhabiting a world created by a thoughtful, imaginative writer (not via e-publications, but actual books) is one of the great pleasures of my life, one for which I always wish to find more time.

Were there any specific challenges in creating the documentary that you didn’t expect? Is there one that comes to mind and can you tell us how you dealt with it?

I had so much good fortune in making this film — from the support of Garry's family and friends and gallery, to the brilliant contributions both creative and intellectual of the D.P. Eddie Marritz, to the help of the Center for Creative Photography (which holds Winogrand's archive), and the support of the teams at Submarine and "American Masters.”

The challenges, compared to the trickiness generally of documentary, of artist biography, were practically non-existent. Raising money is always a challenge, however, and there was a moment when I was quite scared that my Kickstarter campaign for the film would fail. Online, real-time hustling in that way — all the emails and posts and solicitations — was well outside my comfort zone; I dealt with that challenge by leaning on the support and advice of friends and fellow filmmakers who had been there before.

In the process of making a documentary about someone else’s creative work, did you learn anything new about your own creative work?

I learned, from Garry Winogrand specifically, to trust my gut.

As Matthew Weiner says about him near the end of the film: "What you can actually learn from looking at the pictures is to trust your gut. There is no substitute for impulse. You have to have some social skills." I learned all those things for sure.

In the past you have mentioned craft may not be enough in terms of connecting with an audience. What are other skills you consider important for creative people to learn?

Learning how to listen to feedback — whether on initial ideas, written pitches or proposals, rough edits — is a career-long process for me. Sifting out the signal from the noise, honing in on responses from trusted friends and colleagues, but also from near-strangers and sometimes my students, has been an incredibly valuable part of my process in terms of connecting with a potential audience. Find people you trust and listen.

What is something in your industry that deserves more attention?

Although I am a filmmaker, I intentionally operate on the fringe of what most people would think of as the “film industry.” Yet a major issue in the industry of my day-to-day profession — higher education media arts — is lack of real, sustained support for a truly diverse range of voices and opportunities for representation — not dissimilar from, and in fact directly related to, this same issue in the film industry.

If universities and institutions like the NCAA can foster excellence in athletics for minority athletes for example, by making a serious financial commitment to their ongoing development, why can’t we do the same for minority, indigenous, low-income, rural, non-gender-conforming and other marginalized groups who want to — who we need to — participate in media and the arts?

What’s something you used to believe about your craft that you had to change your mind about?

Coming of age in art school in the late 1980s, I believed that strong, interesting, original work would inevitably find an audience.

But today, given the fractured and fractious nature of the way we receive new ideas and learn about cool shit, I no longer believe that to be the case.

I hope I don’t sound cynical — I don’t feel cynical — but it does feel like a new reality that craft is not always enough in terms of connecting with and expanding one's audience.

Can you describe a photographic memory of a moment where everything changed for you?

It is the spring of 1999 and I am struggling to finish my MFA thesis film. I am thirty years old, super broke, and living alone in a studio apartment in Philadelphia.

My younger sister calls often to announce that our parents are worried about my future and my “choices.” Shit, I’m worried too!

Months earlier, I applied for an artist’s residency at the legendary MacDowell Colony, but then quickly forgot about it. One fine May day, I find the Large-Manila-Envelope-of-Good-News waiting for me at home, probably after a day of waitressing (lunch shift, crap tips). I was on the precipice of giving up and that envelope changed my life. I can still see it: rust-eaten mailbox, cruddy lobby floor tiles, the afternoon sun striking the brownstone steps as I race outside to shout at the sky.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Photo Illustration Reference: Zimbio