Sunil Gupta, Photographer

Sunil Gupta is a photographer, educator, and curator based in London and New Delhi. His work focuses on race, migration, and queer issues. His early documentary series, “Christoper Street, New York,” was shot in the mid 1970s as he studied under Lisette Model at the New School for Social Research.

Gupta has organized and curated more than 30 exhibitions, conferences, and lectures. His work is included in public collections including the George Eastman House (Rochester, USA), Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tate Britain, and Harvard University.

He speaks about his first dark room experience as a teenager, the topic of representation in photography, and shares four photo books that inspire his work.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Master of the Photographic Essay,

by Eugene Smith

“When I was in college, I modeled my future around doing documentary work on social justice. W. Eugene Smith struck me as somebody who really dedicated himself. I came across his book and it became a kind of visual bible. It shows you how the guy shot across the different essays. It wasn't just the final essays—actually they aren't even there—it's all the shooting that went on. That kind of detail was hard to come by in print back in the day; I'm talking about the 70s and 80s. I found it very exciting to have access to something almost private.

It was a tool and it was an inspiring one, because all of the pictures seemed very good. I didn't know how you would choose between them. But it gave me a sense of wanting to do picture stories. I was trying to figure out how to do it. Seeing it's way of shooting around a particular theme, I kind of taught myself from looking at this book a lot.”

Un Paese: Portrait of an Italian Village,

by Paul Strand

“I like the way this one is about a place. The idea of a place always was something that appealed to me. About 10 years ago, I embarked on a project modeled after this, in India. My dad comes from an Indian village, so I had access to it in a way that was not just a professional, journalistic way. I could just hang out there. I began to document it, trying to describe something without being judgmental about it.

People look at Asia as a kind of economic powerhouse, but they aren't interested in the villages. They're interested in the towns and the IT part of things. There's not much general interest in an Indian village anymore. I kept looking at it and when I saw this place, I went back to live in India, and I thought, "nobody is looking at rural India, and it's half the country.” Anyways, I did it. I'm sitting on it. Maybe there will be a chance to show it somewhere one day. But it was inspired by this book directly.

I was very taken by the portraits and the juxtaposition of the architecture of the place and the people. I was less interested in discovering things about the place. I was more interested in what he did visually with the pictures.”

Ba Ra Kei: Ordeal by Roses,

by Eikoh Hosoe

“This is a book about Yukio Mishima, the writer. I was aware of Mishima’s work, and who he was, and that whole melodramatic way in which he committed suicide. I thought this book was a great departure from the stuff we talked about so far, in the sense that it was not a social documentary. It was more about his lifestyle, or aesthetics, or the kind of homo-, quasi-, fascistic ideals that he had. It's visually lush. It’s a kind of ‘60s Japanese black-and-white, contrasting photography. It's very theatrical. It's not like the other things that I talked about.

This book opened up a little door that possible to have gay content and it was possible to come from outside of the West. That combination of gay and Asian, it rang a bell with me. It made me think something like this was possible. In my education, I'd never been shown anything like this. I had a very classical kind of education.”

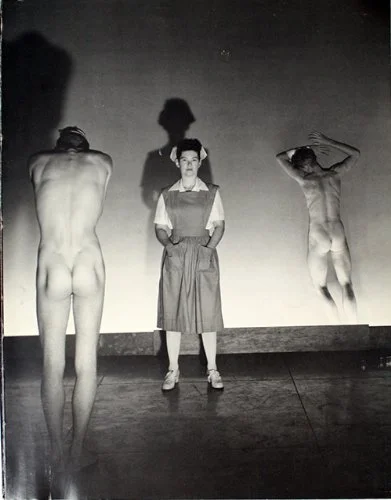

Photographs 1931-1955,

by George Platt Lynes

“This book was very important to me because it already had an existing gay photo history, even though nobody talked about it. It was there. It gave me some confidence to make new stuff, and not feel like I was the only one. I feel like we all got too defined by sex and that's not what's interesting anyway. It's the other things that are worth investigating and having a discussion about—the relationships that people have with each other and their family. This photo book is the one that has stayed with me, and I've borrowed his aesthetics quite heavily.”

Sunil, could you describe the moment where you first fell in love with photography?

I grew up in India until I was a teenager. My only cultural outlet was cinema—big colorful, melodrama from Bollywood. My dad had a still camera. I got very excited by that as I was growing up and wanted to do more experimental things with it. And I had a willing sister who became my first model.

When I was 13, I had a good friend who was also interested and had access to a room in his house. We made a rudimentary dark room, processed some negatives, and tried to make some very bad prints, so it started quite early for me. Then my family moved to Montreal, Canada. It didn't seem like it was possible to do what I did because everything changed. So I ended up in business school, and did photography on the side. I would go to the local shop and say, “I want to make my own prints,” and they would laugh at me. When I was 17 or 18 years old in Canada, I taught myself how to do it through those Time-Life series.

There was an Ansel Adam series called, The Print, The Negative, The Camera—I got all of them. I bought a basic manual camera and a basic enlarger. It cost about the same in those days, which looked a little bit like the ones in the book. I made negative prints in my toilet. And then, I graduated to color, which was fun. It was very off but it was just about possibility. The guy in the shop couldn't believe I tried to do this in my toilet.

There's a lot of things I like about the photography—it has this kind of science, or chemistry, and physics which you could do yourself. So I got myself some scales—I still have them—I got information about the formulas to mix up the chemistry. I got very fancy. I had 2 developers, low and high contrast, and all that. I learned the chemistry, mixed it myself, and made my own prints.

Nowadays, I don't know what's happening, because it's all happening behind the scenes on the computer. I feel like I have no control over it. In the dark room, I know what's happening. I know if I leave it that many seconds longer, or put some little pressure with my finger somewhere, I would get a certain kind of result. But this software business, its got so many endless possibilities. I find it very daunting.

You mentioned that you are already knew that you were gay, but you didn't see much of gay life represented in your education. Was that something you thought about at the time? That you missed?

It's something I missed, and I thought about all the time. Because I was in education at the time of postmodernism and popular culture and a lot of referencing, I didn't know what to reference anything to. The best I could do was maybe "friends of Dorothy", Judy Garland and all that. But my classmates probably wouldn't have gotten it, because I was still kind of slightly underground. There was nothing out in the open, or in the classroom that was talked about.

I could rely upon my peers and my colleagues to have some prior knowledge of it. I felt like I was always explaining it. It took the wind out of the sails, so to speak. It was hard to be funny or ironic if you had to explain it. There was nothing from Asia or Africa, for that matter, certainly not from India. So it became a mission. It gave me a purpose.

I wanted to make work that was going to put my view about being gay and Indian out there, into the world. When I go and talk to young kids now, they're in a terrible hurry.

I keep telling them, "It takes a while.” It has taken me 40 years.

Could describe a photographic memory of a moment that changed things for you?

I remember seeing a guy when I was an undergraduate, and thinking maybe I fancy him, but maybe I don't. I remember this person standing there. I wasn't sure if I really fancied him. It was kind of dark. It was one o'clock in the morning, in a college disco in a gym or something. It wasn't great lighting. I did in fact get to meet him. You kind of think, it's now or never. He is the one who I later on followed to New York City. That's really why I went there and from there on to England.

The consequences were very life changing. He supported my decision to drop out of business school and do photography. I don't think I could have done it without his support.

After 10 years, we split up in London. And then I realized that moving with somebody to another country is not always a good idea. I was suddenly not with the person but in a foreign country. I never thought that that would happen to me. I tried to return to Canada. I think I went to Toronto with my portfolio and they said, basically, "If I were you, I'd stay in London." Because they buy all their pictures from New York and London. So I had to come back and try and make a go of it here.

The consequences of this break up did provoke a set of pictures which I called "10 Years On" about gay couples in London in '84, '85. I used the camera as a way to meet a lot of couples to figure out how I got it wrong. I thought there was something I didn't know. So I used photography to explore and meet people. I made about 30 to 35 portraits like that at the time. I didn't find out anything though. There's no answers as to why people are together.

I started with some lesbians, but that ended very quickly because those were quite separatists days, in my experience. Women did women. Everybody was very politicized and angry. And they didn't really want guys to do girls kind of thing. Gays with gays, and blacks with blacks, at least that's how it was. You couldn't really go over to the other side and do something.

How do you feel about this concept you mention, where people can only photograph others who are in the same group as themselves?

This is a complicated discussion. I feel like people expect me to photograph myself. Chicken and egg. I put myself in a specialized area where I'm working with gay, non-white subject matter quite a lot now since I've left school. It's partly because I felt like it wasn't being done or being done from our point of view. The points of view became very important in the discussion.

The other thing is that westerners are able to travel the world and do all this photography of people who can't do it back to them. It seems a bit uneven. Sometimes I'm irritated by travel and photography. I was guilty of it too. When I lived in London, I used to fly out to places for a few weeks and take a bunch of pictures and come back and sell them in a story or something. That way, all you get is a clichéd, surfaced vision.

For example, if somebody from the US, who was not a person of color, would go to India and shoot my subjects and come back. Those photographers might have much better access to the whole infrastructure of exhibiting and publishing. So in a way, I'd lose my subject to them. It's a tricky thing.

To come back to your question, I think it's a very short period where there is a kind of balancing happening. Hopefully, at some point, when it has happened, then it won't matter. But I don't think it has happen yet, so it does seem to matter.

When I was an undergraduate, in the late ‘70s in Canada, there was a form of affirmative action of only hiring women professors because they were hardly any. It was a tough time to graduate if you were a guy, because they were no jobs. You had to migrate to the US or Europe. They have balanced it now, they've stopped doing it. But now they've got a much better gender balance in the schools. Sometimes it takes something like that.

It can get very essentialist. I'm a bit weary of that. It also means that black people can't take pictures of white people. That should be odd because there's a lot more white people around. Like in my pictures of Christopher Street, I wasn't thinking racially, I was thinking gay. So whatever was there, was there.

There's a subgroup of people who are gay and of Indian origin who live in the US. Sometimes when they hear about this book, they contact me to say that it makes them feel seen—that an Indian man who's done the work, it validates a little bit of that experience. Because otherwise, they'd never see themselves doing anything.

The representation is what matters to them?

I think it's not just race. It has to do with power. What I'm seeing in some black friends of mine, in the UK and in the US going to say, Africa, the black people in Africa aren't that thrilled to see them just because they're black. They’re viewed primarily as westerners.

They have access to power and money. They come with technology and equipment. And it prevents the local people from doing what they want—to document themselves. There's a lot of friction there. It doesn't come up that often, but I've seen it happen.

I think it's more to do with power and access and less to do with actual color.

Could describe a moment or a time where you felt creatively stuck, and what you did to get yourself out of that creative rut?

I think I have a slightly cheesy answer to this: I just buy a different format camera.

A while ago, I bought a Speed Graphic. I tried to do free photography with a 5x4. That was a disaster. I don't know how it was when Weegee did it, but I guess they used a flash.

That didn't work for me. I used to be 35mm TRIX kind of guy, and then suddenly 10 years later, I became all Hasselblad, flash, and color for a while. And then, I go back and forth.

When you changed from one format to the other, you had a new boost of creative energy?

I think so. Once I was feeling very low, just generally, and I got one of the Hasselblads for the first time. I just went around the park taking pictures of shrubbery and things, not things I normally do. And I was just blown away by the detail of it. I thought this is the kind of photography I never really looked at properly. It was so sharp and detailed. I began to accumulate equipment like this, by suddenly changing them sometimes.

I stuck with the Leica in the 70s and 80s, and then I switched. Hasselblad became a little bit bulky, and then I found something called Mamiya 7 to be a good one to travel with. I documented my Indian village that way because it was a rural setting where you walked around. I didn't want to stand out like some big pro with a lot of gear. I used to use Polaroids to test Hasselblad shots. Then I began to use the digital Nikon to do that testing. They got so good that one day I thought, "I can print straight from this digital frame.” I thought, the testing I'm doing on the Nikon digital camera, that can be the final image because the quality became good enough to print reasonably sized prints from. So suddenly the Hasselblad became a little bit redundant because the digital was getting the data.

When you put together a project and a series of images, what's your process like for telling a story, for creating a narrative?

It's little bit colored by the fact that I got involved with editorial work in the 80s. It was all on transparencies. Physically, it became 20 images, 20 slides. I think because editors like to see them in that way, a story became 20 pictures that you would offer them. And that would reduce to maybe 4 or 5 pictures in the magazine.

From that, I've carried this idea that there needs to be 20-30 pictures around a project idea. So when I was doing the gay couples, I needed about 25 or 30 or it won't be complete—that's what established the number.

Sometimes the sequencing matters, like how they follow from one to the other. Sometimes it matters a lot, and then other times, like Christopher Street, I was less concerned about sequencing. The publisher did it. And I was fine with it because there was no narrative from the first picture to the last picture. Every picture was a separate picture. In that sense, it wasn't going from one picture to the next. It wasn't building up to anything.

Some of my friends are very obsessed with the sequencing, especially in books. I've spent some hours with them. They have the tendency to rope everybody into their editing project. Hours looking that screen trying to sort the pictures out. It's definitely a skill and it gets better over time. That's why I tell my young students that it's hard to explain it. It just gets better over time. I've seen so many pictures, over the last 40 years. It;’s hard to explain it how you know how what goes with what sometimes.

I've gotten more or less involved depending on the nature of the project. Some people want to be completely involved with the design. I'm not a book designer that way. I appreciate that designers have their own kind of skills, because they do it all the time.

Is there something right now that you're trying to learn or master?

I've become interested in archiving. That's my current project.

Starting with my own archives, I'm working on a retrospective show which would open in January in Toronto, which will feature my photos from 1973 to present. So aside from the show, I was discussing with the curator that instead of having a photo book, because there's already been some, that maybe it's better to try and get a print version of the archives idea.

What is something in the industry you feel that deserves more attention?

I think the history that we learn needs to be more globalized.

In London, my students have become more globalized. I have a lot of students from east Asia for example, Korea and China. And they feel they're not being taught about where they come from. We don't know enough about it. I've only been once to China to Lianzhou Foto Festival. I was amazed at how much was going on there, and how little I knew about it. I think we need to know more about it over here. Nobody is bringing that information over here. It only happens if people turn up.

What are your views are on the role of the artist in society, and the impact that visual arts have on culture and perception, especially today in this world that we have right now?

I think the role of artists is to ask difficult questions about the future of humanity. What kind of world do they want to live in? When I was doing editorials, I became aware of the limitations of putting stories out that way to raise issues. Everything is controlled by the editors who are in turn, controlled by their publishers and the owners.

I think only artists and scientists can tell us what the future is going to be, or should be. But instead, what we have at the moment is a bunch of corporate managers telling us how it should be. That's a big problem.