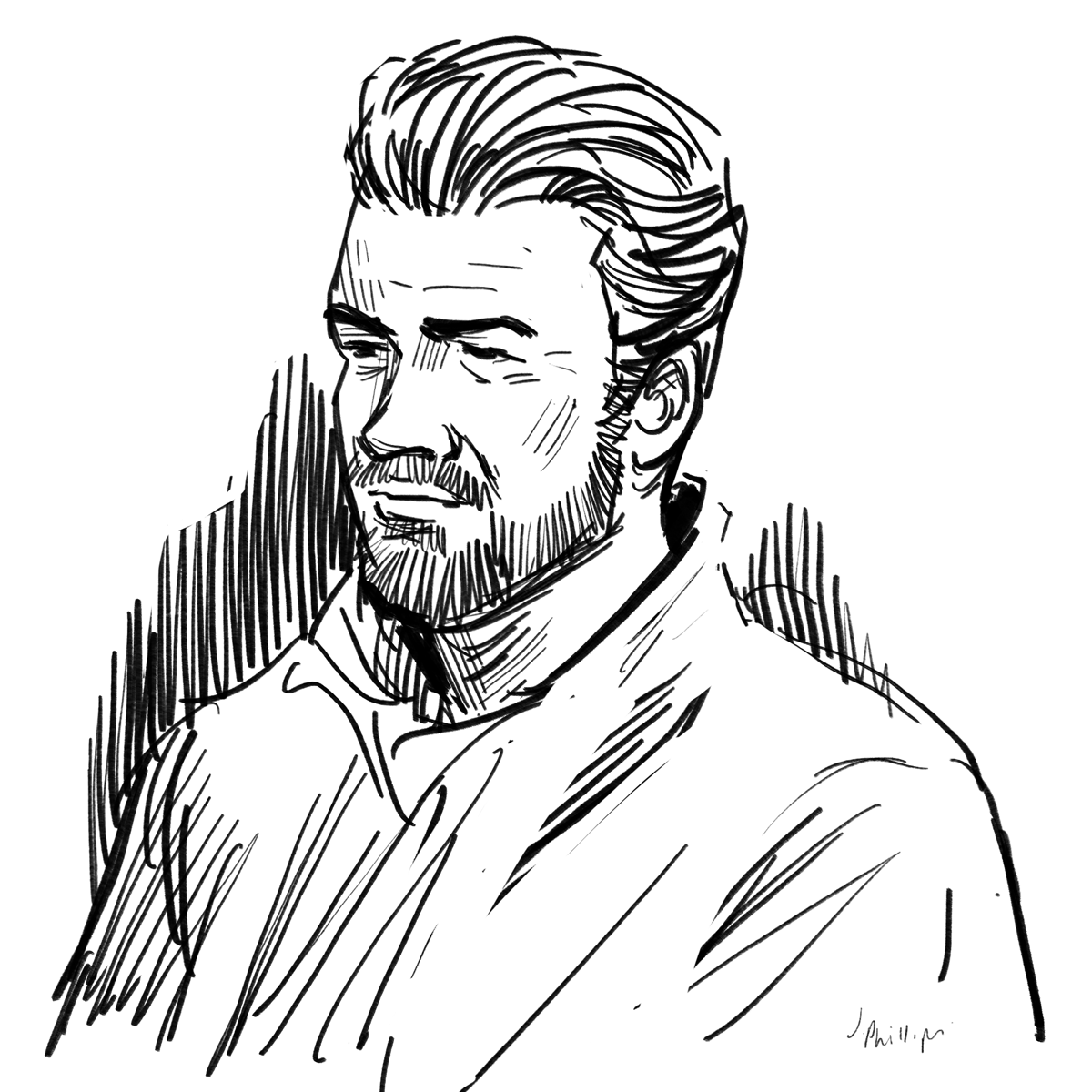

Robert Clark, Photographer

Robert Clark is a photographer based in New York City, working with the world's leading magazines, publishers, and cutting edge advertising campaigns, as well as the author of four monographs. During his twenty-year association with National Geographic, Clark has photographed more than 40 stories.

Early in his career, Clark joined author H. G. “Buzz” Bissenger and documented the lives of high school football players for the book Friday Night Lights. The best-selling book was later made into a major motion picture as well as an NBC television series.

Clark shares 4 photo books that inspire his work, a photographic memory that changed his life, and how he has dealt with constraints in his various assignments.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

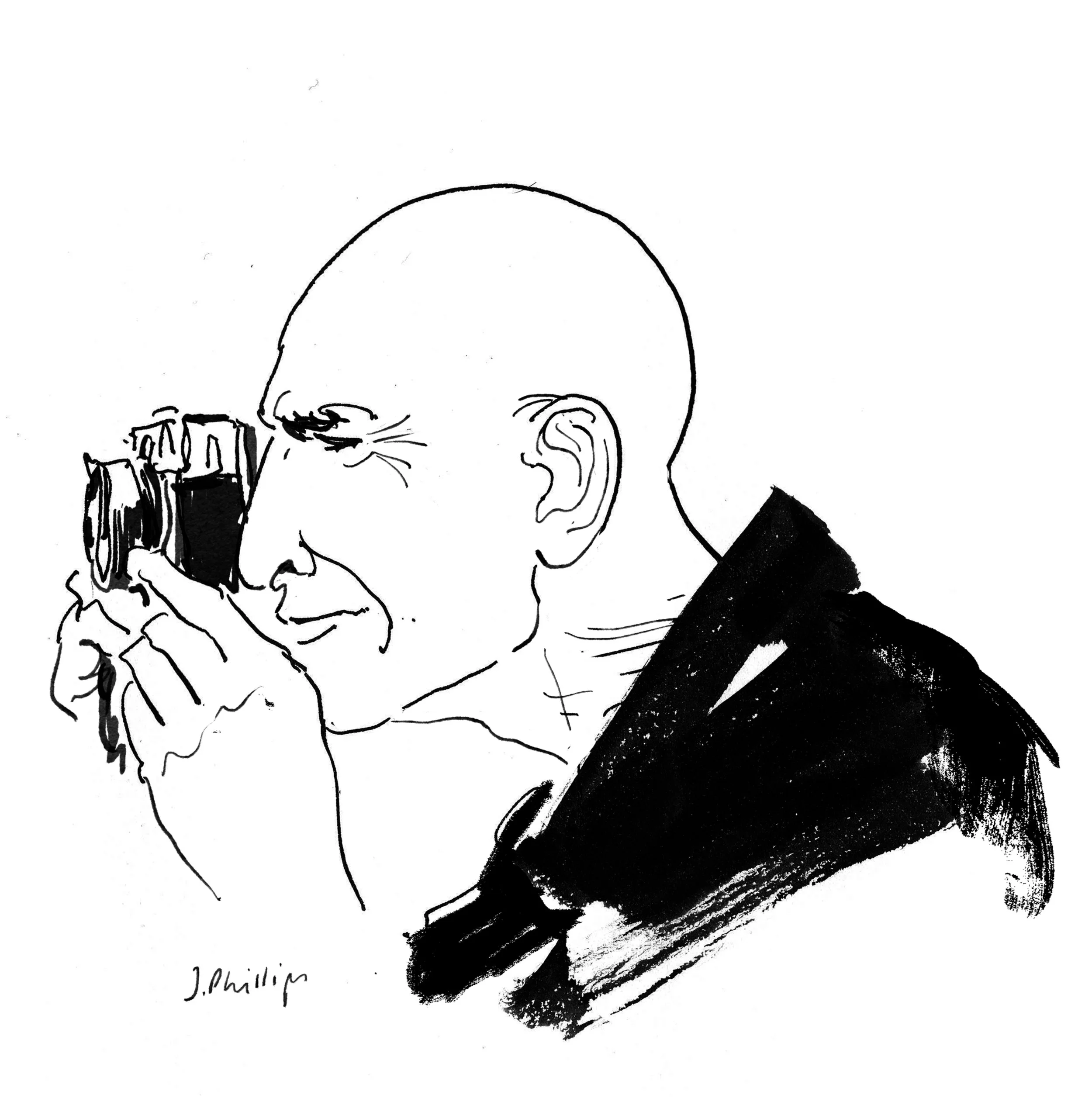

Cyclops,

by Albert Watson

“It's kind of a collection of his portraiture and advertising. And I was lucky to meet him. What I liked about this photo book is the diversity. It’s beautiful still life, beautiful portraiture, and I have a few books of his. I think one of the things that's always been most important to me is composition. Composition is changing because of the cell phone. There’s more freedom to it because most of the people doing it aren't formally trained in photography.

Maybe the problem with my photography is the rigidity of it. I think cell phone photography has loosened me up to composing and shooting pictures for a specific visual narrative that you're trying to fulfill the requirements needed by a magazine. I think it's fun at some points to just kind of loosen up and shoot what you want.”

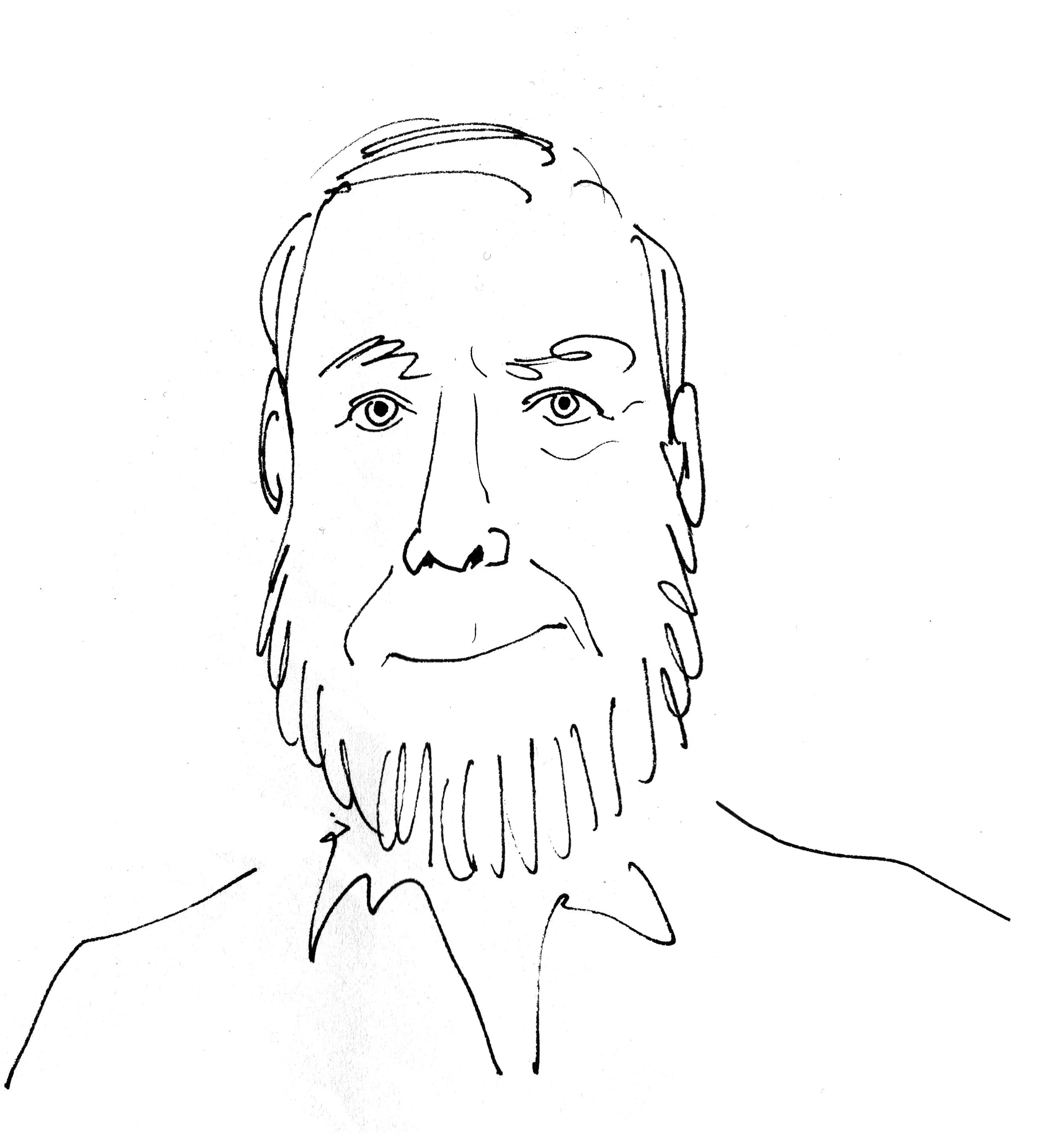

The Road to Seeing,

by Dan Winters

“Dan talks about composition in his self-portraits and how he also pulls in a lot of historical examples of photography. He talks about other people's work, why it's important, and how it influenced him. I was attracted at first because of the technical ability of it all. It's just like Martin Schoeller or Albert Watson or Richard Avedon. I got sucked in because of trying to understand the technical aspect of it—and then you sidestep the technicalities of it and you see the beauty of it. I think the palette that Dan is obviously known for is a palette that he kind of works in and created for himself. In terms of the pictures in the Road to Seeing, I think that his personal pictures are the ones that really stick with me. They are just beautiful.”

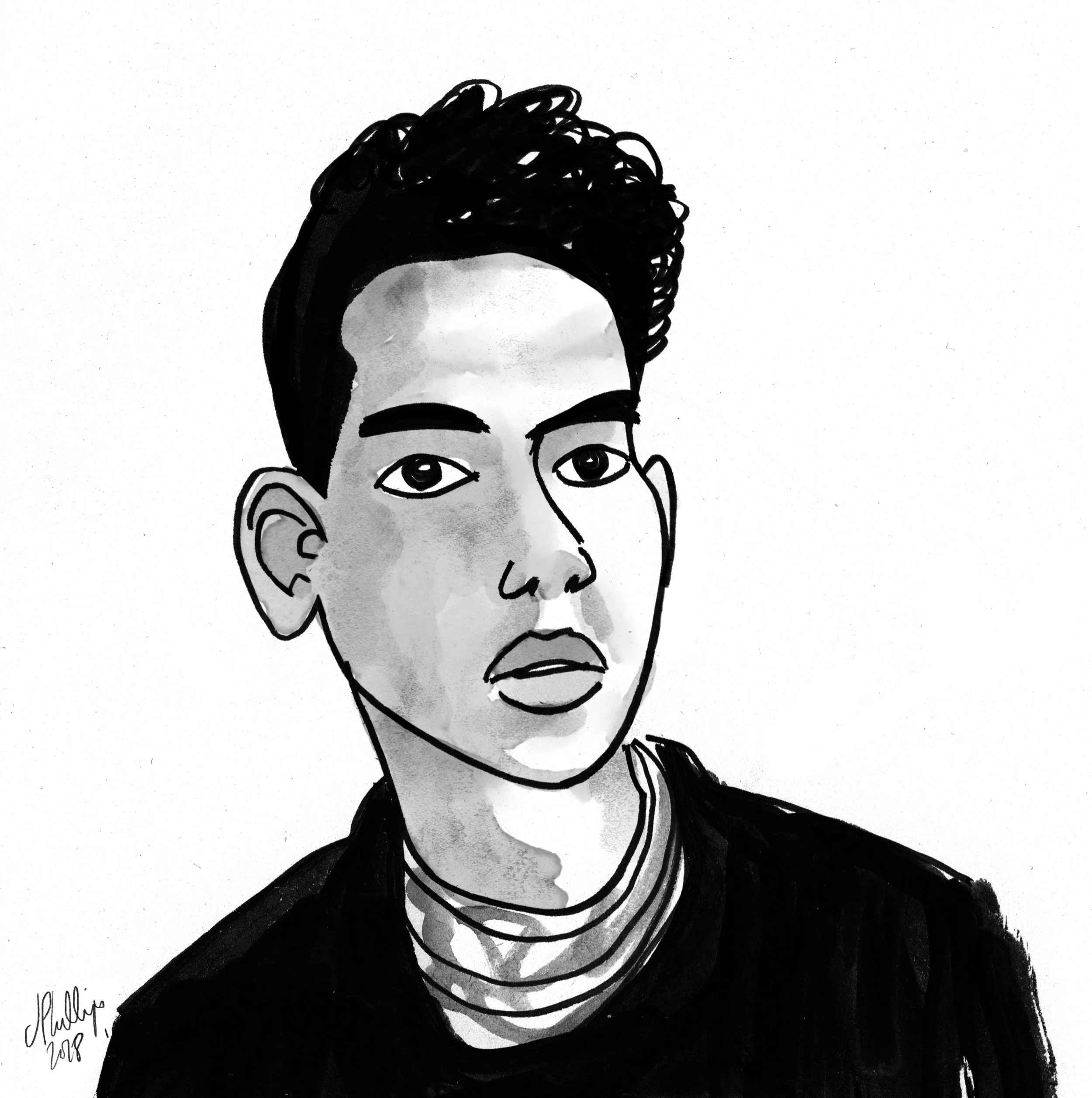

Son,

by Christopher Anderson

“Chris's book is interesting because I think that one of the most important things a photographer can do is to turn the camera on their own world. He can find the intimacy of stuff and his use of color is phenomenal. If you look at Approximate Joy and his Instagram feed, there's just so much interesting work in color. I'd love to be able to do more of that—maybe as I get older and things kind of disappear. I've got a nine year old daughter and I've photographed her extensively, so even though a lot of it's with the cell phone I think that all of it will be historically interesting. If I could change anything about my career, it would be what I love about Chris's work, in that he's able to turn the camera inward.”

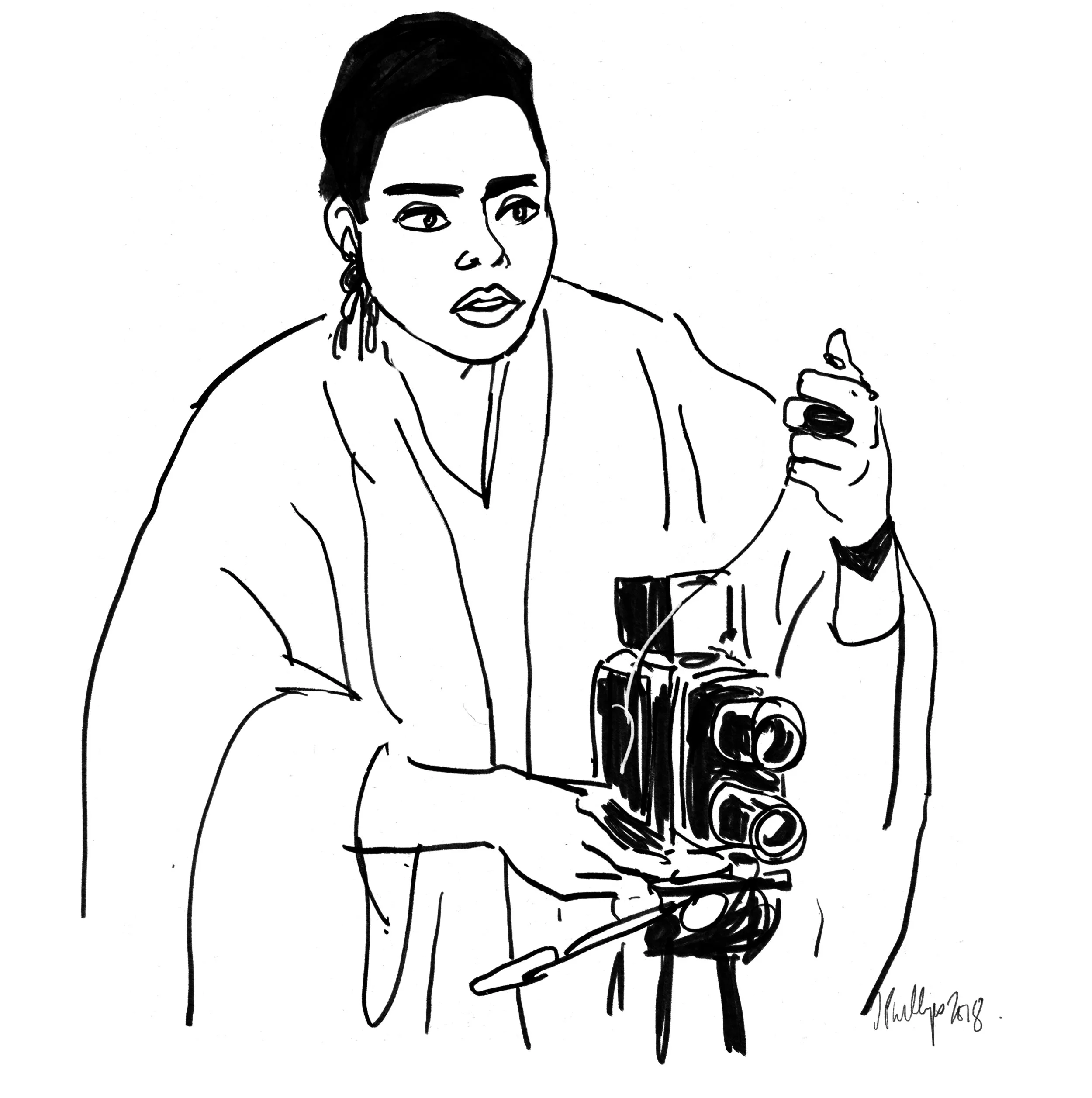

Indian Circus Book,

by Mary Ellen Mark

“I love how she used the environment as a backdrop, like a tent. For me, it was really interesting to see that a master like Mary Ellen was inspired by photographers like Diane Arbus. It's interesting to photograph a subculture. I think that's a cool thing to spend an extended period of time shooting one culture and just getting different aspects of it. And the circus is its own thing.”

Earthly Bodies,

by Irving Penn

“This is the work of a true master. He did personal pictures to kind of renew himself. He was doing a lot of magazine work for people. I love the fact that he went and did this different body of work.”

Robert, what advice do you often share with young photographers?

Young photographers come to me all the time and ask, “how do I have a career in this business?” And I say, "Well, I don't know if this business is going to be the same." But I always say learn as many computer programs as you can and learn it really well. But also get the biggest cup of coffee you can get and go to The Strand, to the book section, and just sit there all day. Do it every day for two weeks, just look at photo books, and then you're going naturally gravitate back to the ones that speak to you. And I think that'll help people understand and figure out their own voice.

I've never really pursued advertising at all, but I want to shoot things that go together, that hang together. A lot of the stories that I do for National Geographic are very diverse. The only thing that you can do in filmmaking is to develop a through line to where there's a connectivity from one image from the first image to the last image. That's really important to be able to do. This mindset has been helpful to take a science story that doesn't look like it should go together and then weave it together with the same palette and the same kind of lighting that make it a visual package, that makes sense in terms of a magazine design and layout.

It's really hard to have a career now. I think the reason that I have been successful is because I worked at newspapers before and I had failed hundreds of times before when nobody was noticing. And then I was able to move into magazines. A lot of people who were assistants or people I worked with when I first got to New York, they're not in photography anymore.

I can name 10 people that I knew who were kind of moving through the photo career when I was like 32, so early 90s, that are photographers that are still in the industry. You have to want to do it. Certain photographers whose work I know, I tell assistants to go do something else a lot of times. I look at their pictures, and unless they're kind of figuring it out, I say, I don't know you might want to go do something else.

The photography career is about persistence in a large sense. You will have so many failures and disappointments and negative feedback. We're all insecure enough anyway, and to get something you think is great, and then a photo editor or an art director tells you it's not great—I think it’s about learning to deal with that rejection, which is super important.

Throughout your career, you’ve dealt with both low and high budget shoots, different environments and cultures. How has that pushed your creative process and what have you learned about working with constraints?

Sometimes, no budget and a limited time to complete something is an advantage. I did some pictures of bog bodies for National Geographic. It was a very specific kind of mummy in the Iron Age period. The assignment was in Ireland, Germany, England, Denmark—a handful of countries. I did this story in 16 days.

It wasn't necessarily hard to do because lightning the mummies or artifacts was something I was really comfortable doing. It needed to be done; they needed an archaeology story, because there weren’t many of them assigned. Susan Welchman and I had tried to do that story 15 years earlier, and it just didn't happen. I then went and did it, it was great, and they ran it beautifully designed. They do a rating system at the end of the year and it was one of the top five or seven stories of the year. It was quick and easy, but it was about the subject that was so compelling.

The photography was fine, it wasn't earth shattering. These things have been photographed a lot, but it was really interesting for me personally. There's an Irish poet by the name of Seamus Heaney, and he wrote poems about the bog bodies. We ended up using some of his poetry as captions, which was kind of lyrical and beautiful and really smart on Geographic’s thinking.

Realizing this, how have you dealt with this or what can photographers learn from this?

Maybe it’s how I was raised, being from western Kansas—like who do you know is from western Kansas? Why do you think I should be able to do this? I'm not from New York, I didn't go to art school.

Persistence is the game. I ran cross country in track and I wasn't great. The only thing I learned is the only way I got better was to run more and train more. If you want to be a great runner then you have to put in hours of running—the wider your base, the higher your peak.

The more you know about photography, the more you shoot pictures, the more different kinds of photography you do. It's going to make all your photography better. It's a lot of hard work and you have to want to do it. I don't think most people will want to do it as bad as they think.

And there's people who get recognition, and then you never hear from them again. There's people like Chris Anderson and Wayne Lawrence who just keeps producing amazing work. They do one thing, and then another thing, and another thing—it's just this continuous building of their body of work that all relates to each other.

Once Richard Avedon started shooting stuff on white—he did a lot of stuff before that—he started doing that then all that work hinges on one way of seeing. But I also look at it and go, it's not about the photography, it's about that way the picture becomes about the subject.

I've accepted the fact that it's really more about the subject when everything is stripped away. Because there's an intimacy, like in the American West. I think that's what photography is about. It has turned into this transactional thing: I produce this, you pay me this, I get another assignment so I can produce this so you can pay me this, and so on.

Do you have a photographic memory of a moment where everything changed for you?

When I shot Friday Night Lights and then Sports Illustrated ran 15 or so pictures in black and white photos in it—that was a big deal to me.

It was unusual and it was a kind of narrative photojournalism, so I was able to follow this team. If I had to do it over again, I would move to Odessa, Texas and I'd spend a year there. I had like 80 rolls of film from being there for a few weeks and the pictures are good, I think, because of the intimacy and access I was able to have. I think that was important.

What is something in the industry that you feel deserves more attention?

When I was young, I started to see the rise of Annie Leibovitz from Rolling Stone days and how her work changed over the years, the refinement of it. And with magazines, it's all about real estate, it's about how much space is given to certain things.

There's been this disappearance of long term narrative photojournalistic projects, which I think change the world, and not in the corny sort of way—I believe that images have impact. They matter. Narrative photojournalism matters and it's also interesting that shorter films and different video formats are having an impact now too.