Joseph Rodríguez, Photographer

Joseph Rodríguez is a documentary photographer and educator born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. He studied photography at the School of Visual Arts and in the Photojournalism and Documentary Photography Program at the International Center of Photography in New York City.

Rodríguez’s eye is drawn towards social documentary and capturing the struggles of everyday life. He is an Alicia Patterson Journalism Fellow and his exhibitions have appeared at Galleri Konstrast, The African American museum, the Walter Reade Theatre at the Lincoln Center, and many more. He’s also the author of six photo books, including the beloved Spanish Harlem.

He shares three photo books that inspire him, and tells us about his experience teaching photography, debates the age-old film vs. digital conundrum, and tells us about the project that meant the most to him.

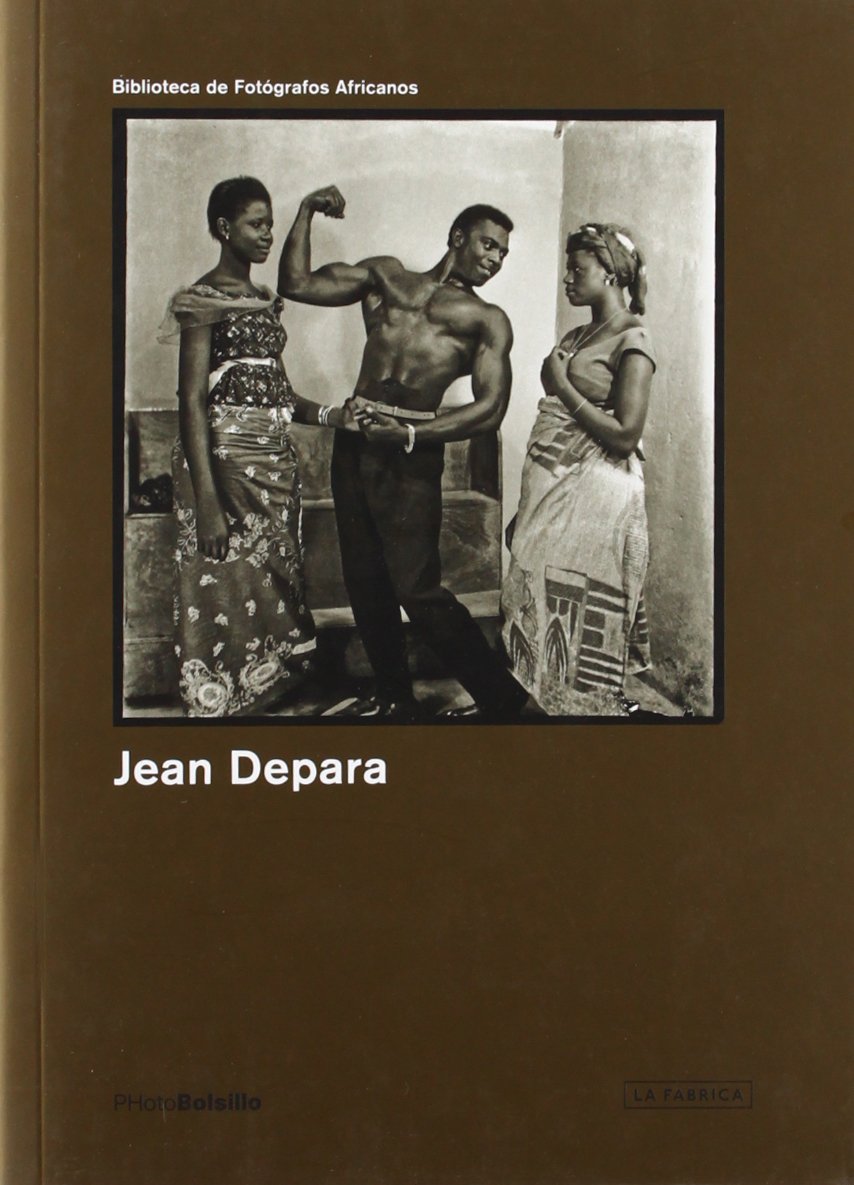

Jean Depara,

by Jean Depara

“Before taking off on any long project, I always look at other works. What inspires me are photographers that are not even of today, they're photographers from before. And how I discovered Depara's work is through the publisher in Paris called Revue Noire.

They cover photography in Africa, and it's a beautiful historical publication of African photographers. I had been looking at the content now for the last 25 years because I've been to Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Mauritius. It has to do with the way these photographers look at themselves and their cultures. That is something that goes back deep into Joseph Rodriguez' photography, going way back to my first project in Spanish Harlem. I want to own my own story. I want to tell it in a way that I think is more intimate and perhaps a little bit more subjective.”

Raval,

by Joan Colom

“Joan Colom is a street photographer from Barcelona, and I bought his Steidl book some years back. This guy approached shooting on one of two streets in his town; he also went into the bars. There's a lot of sex workers today in this alley. He used a Leica, and a lot of the times shot from the hip or shot from the side. I just love the moments that are in there. It's just ... oof.”

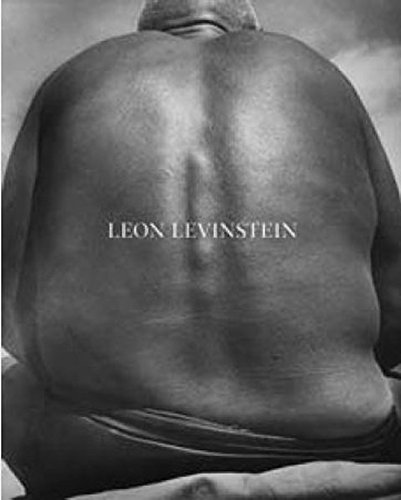

Leon Levinstein,

by Leon Levinstein

“I've been looking at his work for a long, long time, ever since my discovery of the Photo League. What brought me to his work was the fact that he was shooting 6x6 and was a graphic designer by trade. His compositions and connections to street photography were amazing.

I had struggled early on because we all take those large format classes at ICP, right? And then you start thinking, wow, maybe I can make some interesting portraiture with the square, or we can do this or that. And also being a New York photographer, I really connected to his work.

I picked up the square in 2000 when I started the juvenile project. I saw what I could possibly do. I needed something light, so I picked up a Rolleiflex, then I decided to try to get closer, so I put a + 1 on. I learned this from Levinstein. I wanted to get as close as I could with the camera.

The 6x6 format can be conservative. People tend to put everybody in the middle, almost like a Velázquez painting. I was trying to see if I could change that up. And that's where Levinstein’s compositions were killer. We always hunger to be better than who we are. Looking towards his work was something ... I'm still looking at it. I just looked at it just a couple of days ago. Not to copy, but to be inspired, to use his work as references.”

Joseph, you graduated from ICP and now teach at different schools. Can you share an experience that continues to inspire you today?

When I was a student at ICP in '84-'85, I had the great opportunity to study with Fred Ritchin and all the other Magnum photographers that were teaching there at the time. We were really blessed. One thing that always grabbed me when I had to do our history research was how much fewer books there were from other parts of the world. Fewer books from Africa. Fewer books from Latin America.

When I started teaching at ICP, I bought so many books and made copies—this was before digital—to share with the students so they would see that there are many more people in the world besides what we're being taught, which is mostly the European school of photography. This was all at Magnum; there's hunger there. And when you have the hunger, you're always searching for artists or life that sort of maybe connects to yourself.

I even remember talking to Phil Block back then when I started teaching. And I made all theses copy slides which I donated to the school. We don't use them anymore because everyone uses the internet. They became important, I think, as references—to be able to open up what else might be there for us.

How would you describe the difference in learning photography in different countries? And how did it change your way of shooting and connecting with people and cultures?

I had worked in Mexico a long time so, naturally, I discovered Mexican photographers other than the ones that became very famous. There's so much rich work down there. It's the culture and how people live. I'm more interested in humanity, so I'm not always interested in, as a photojournalist, in shooting the problem. I want to be shooting life.

I was hungry for that. A side note: moving to Sweden for five years and then going back for the past 20 while my children were there—they’re grown up now—that was inspirational because I met Anders Petersen and became friends. He never shot flash before. He was a master of pushing six triads at 1600. He taught me how to do that. And that's when I got involved in Romania. It was just a really beautiful time for me.

In terms of also opening up and getting away from the American school of the documentary which was more, “Where’s the problem? Let’s document it and see if we can get that message out,” which I'm still very much a part of; Dorothea Lange is totally in my heart. Moving over to Northern Europe and around actually broadened my vision a lot more than me being an American photographer.

In Sweden, the approach was quieter, softer, more emotional, especially if you look at Anders' work. That was a challenge for me. I learned a lot from them. I also went to Finland and Russia, discovering more photographers along the way. I just was hungry—you know how we are.

American School of Documentary tends to be more about the issue. Where's the story? Where's the problem? Let's look at the issue: war, poverty, illness, etc. When I got to Sweden, they were also concerned with those issues. But, for example, in Sweden, they would never put a dead body on the front page, ever. It's just not there.

The challenge was, how do I make an emotional, powerful picture that doesn't necessarily have to show blood and guts? Because here in the states, all the contests were driven by that issue; even the world press is still that way. I started to lose a little bit of faith into the way photojournalism was working, and then Anders had a different approach, a slower approach like Asa Frank and Hakan Ellison. They hung out, they drank wine, they lived with the people. They got these beautiful warm moments which is not always easy to do in photography.

I think that opened up my eyes quite a bit. They were strong black and white photographers, before all this color and magical stuff came in. I had a lot of climbing up to do. And then I joined an agency in Stockholm called Mira that Anders was also a part of. The beauty of being in Stockholm was that it was small—four photographers got together and shared a lab. We could rent the space. It was a very different approach. And at that time, going to Vietnam from Stockholm was the first trip that I ever did in my life.

We’re seeing this momentum where many photographers are going back and learning film photography. The essentials, as you previously described it. What have you noticed in shooting both mediums?

I started out with a Leica M2. First Leica anyways, as a wedding present. 35 f/2.8 Summaron—great lens.

I think the Leica is something that a lot of younger photographers are becoming very excited about in this younger generation. I think they see that thing about digital photography: everything looks the same.

The point of focus is so ultra sharp. Our eyes don't see that way. I like to take my students—when we used to be across the street at the museum—and go upstairs to the printed collections to see the great photographs. Ninety percent of them were not that sharp. So nothing looks the way this surreal, ultra sharp world of digital photography, which has become the new norm.

Even looking at the current Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibit, half of them are definitely not in focus.

It wasn't about that. That's why I'm so blessed because I had the teachers that came before me. It was really about the moment and also about that image, if you can create it at the time.

We get to use the bells and whistles of the technology of photography. Keeping it simple is not a bad idea these days. Going back, well, there's this kind of economic philosophy. We've been living this way for some time, but we think very German in the way that, if we want to have something, we save for it. We don't do this the American way and spend all this money on something. Taking your time, using that philosophy to be smart about how you best want to work, and what makes sense to you. Because you know how it is when you're young: you follow the path of everybody else.

My intern just went and bought a Horseman 4x5 which is a great, strong camera. But yeah, I think you're right. There is a new wave now where people are getting into film. It's the compactness of it all. Keeping it simple. Thinking about what's in front of the camera. Don't get too caught up with all the technical stuff. Most importantly, for me, when you ask about what books inspire me or what books I've been looking at lately, it really is about digging deep into the history of the photographer.

Why is that important to the craft?

Most young photographers think that photography started with the digital era. So they look at— if they're photojournalism doc people—they start looking at the new photographers.

One thing that I've always felt very strongly about is understanding acting very well, especially here in the United States, the method acting school. The Strasberg School.

If we think about acting today, we think about Hollywood. If we see who's acting and who's coming out of those schools, a lot of them are British, Irish, and Scottish actors/actresses. Why is that? That has to do with the fact that they go way back when they start their education. They know their history in terms of Shakespeare and others. This really has a lot to do with why their acting is so good. It's because they're theater trained.

The same thing for the painting school at NYU. They went way back to the 14th and 15th-century painters. That makes you a better artist. Same thing with writers.

But the thing about photography, because I guess there's so much of it, we tend to be overwhelmed and we grab what's in front of us. But if you really can grab the history and live in the moment of those days—not the attitudes or beliefs, per say—it just makes you a better photographer. I really feel that way.

Earlier you mentioned a painter, Diego Velázquez and his composition. Can you tell us more about this inspiration that has influenced you throughout your career?

It's a Taschen book by Nicholas Wolf and Diego Velázquez, containing many many Velázquez paintings. I've been looking at his work for a long time.

I've been blessed to have met the Taschen family because I'm represented by them now, so we're very close.

Here's what I love about the family—and I mean his father and his grandmother—it's about looking backward. And then you look forward. That makes you powerful. That makes you much stronger.

The person who taught me that is Gilles Peress.

Do you remember a moment where you felt you were learning that lesson?

Yeah, the minute I left his class. I was just his TA but he was the one who came up with this great idea.

This was the assignment for everybody. It was a weekend workshop: Collect 100 images you wish you would have taken.

I've been doing it for my students for 20 years. I just saw Gilles a couple of months back and I told him that and he was laughing. That really solidifies us.

We can teach you everything but the one thing we can't teach you, which is what he said, is what you care about. And what you care about is what you spend most of your time photographing. But looking back is very important.

When Gilles went out to do Telex, Iran, he went because he was the only one to get a visa for it (because he was French). Also, what book did he have in his back pocket? He had the Koran. That's it. He's a man of history, a man of art. The other thing that really blew me away about Gilles’ work is he had a big show one time in Madrid with Picasso's great famous painting next to his Bosnia work. That blew me away.

It's how he thinks about photography. Not just literal, right? So going beyond what you're photographing. Can it be timeless? Can it have weight? Can the portrait pull you today like a Velázquez painting? That's what he would say. That's what kind of messes with you. I think we try to hold onto those traditions.

What is something in the industry that deserves more attention in your opinion?

It's a big question. Some people might feel that in this industry there's not enough attention, what you were just saying earlier like maybe there needs to be more attention for painting. But some people might think there needs to be more attention to something else that you said earlier, photographers of color that haven't seen as much of the success.

I think that has been coming out in the industry. You can see it in PDN. You can see it Aperture. The world since the internet is much more open than it used to be. People still get a lot of references on the internet by putting it on Instagram.

I think we need, what I think I'm hungry for, are photo editors. A while back, a photo editor that I worked with who I really respected, said to me, there are two kinds of photo editors. Photo editors that work for the company and photo editors that work for the photographers. And I really feel that we need photo editors that work for the photographer.

I think about Bob Pledge. Robert Pledge from Contact and the amount of energy that he would put in. He's running an agency but he's really an editor. He taught me about editing, that was stellar. I don't need an editor. I haven't used an editor for a long time. Every book you see I’ve edited myself.

I think it's important to have those professionals in the industry. The industry has shifted so much that the weight of a photo editor is not as strong as it used to be. They're the first ones to get laid off. And now they want photographers to do everything. So we do everything. There's a hunger there.

The other thing I think about the industry is the lack of curators. That's a big story that's been coming out in the arts pages in the New York Times recently these last couple of years. The grants, the same thing. There's kind of a default. It just doesn't leave the opportunities to be more open, to discover. You can see it in photographers like Jamel Shabazz, just to name one. There are many of them out there. There are a lot of great things that happen in photography since the whole digital revolution, really. It made it more democratic. More people can get out there. This conversation we could really talk for a long time. But there's quite a bit that's been shifted.

Do you have a favorite project?

The most important one. And that would be Spanish Harlem.

That was the place where I first photographed my family. The most intimate work I've ever done in the beginnings of my life. Just recently, I've found the people that I've been photographing that is on the cover of the book, 35 years later.

I'm a guy that kind of likes to look back. Not for everything. I would say Spanish Harlem was the most profound experience I ever had in my life. I'm basically coming out of school—a lot of challenges there. Learned how to shoot color. Learned how to get to that, beyond the door. Because shooting Kodachrome then was just like heaven. I hope they bring it back. They've been talking about it. That would be wonderful.

The other project that would probably be the most challenging was the gang project. I almost lost my life; I had a contract on my life. That was excruciating and difficult. But I can tell you if I go back to Spanish Harlem, there was a moment with the Rodriguez family.

Sometimes in my point of view, it's about helping people. I always feel I lived that moment. I lived in a family like that. Where people were fighting and stuff like that. I hope that was helpful.

What is the best piece of advice that you've received in your career?

Two people. Gilles was one; him putting me in a corner. After that 100 images assignment, which we would have taken, he laid them, he was like a psychiatrist.

He would pull you into the classroom. You'd sit there by yourself. He'd look through your slides. And he'd look at my slides and he'd say, "Why are you so angry?" And I was like, "What?" And I got very defensive. But it all made sense. I said, "I'm angry because I grew up in America and I've lived through a lot." I'm 67 so I've lived through a lot. Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy, on and on and on. Social justice goes deep in the foundation, so that was profound.

To this day, it's still the same. So I would have to say him and then I would say Fred Ritchin because we were close. Fred was not just a teacher—he taught me life. He said, "Joe, I'm not gonna teach you photography. I'm gonna teach you about life." And so, everything I've learned I've just passed on to my students now. I think those were very valuable contributions to my journey.

Was there anything in particular that Fred said as a piece of advice that you recall?

He said, "The most important moment for you is to photograph what's in front of the camera."

Today it's the complete opposite, you know that right?

How would you say?

Today, it's about the photographer. Look at us. Look at us on the internet. Look at Instagram for example.

One of the frustrations I have about Instagram is that people just throw pictures up there like, "Oh look at me, look at me." But does the picture have any weight? Does it have something to say?

Street photography. I think Instagram's great but street photography is taking a serious dent. All the flood of, one thing looks like the other after a while. It's not difficult to do a street picture. All you gotta do is hang out. You get the right light. You get the right moment. But to go knock on a door and to go inside? And to connect? Yeah. I think that's not easy to do.

And if you do that, then honor the subject that you're photographing. That's what Fred taught us.

That's very important and we totally share that frustration about Instagram with you. It's become almost like a commodifying factory of our schedules.

It becomes a hobby for people. But, in your case, and in my case, if you're gonna post, post what you care about. If you go to my Instagram, you're not gonna see me where I'm eating. You're gonna see just one project at a time. That's it.

I tested the waters with my project, Migrants. First, we started with the everyday incarceration project. And then from there, we went on to LAPD and you start, with migrants, for example, I took months for that work. The kids from Mexico and the Mexican kids from America started to come back, like this is the history. This is how young people see the world. There was narration to go along with the pictures. I used that platform sort of like a little history book, that's all.

Have you found that people respond to you differently now that you're an older photographer versus when you were a younger photographer?

Oh, that's usually always the case.

It takes 10 years to be a photographer before people start to take you seriously.