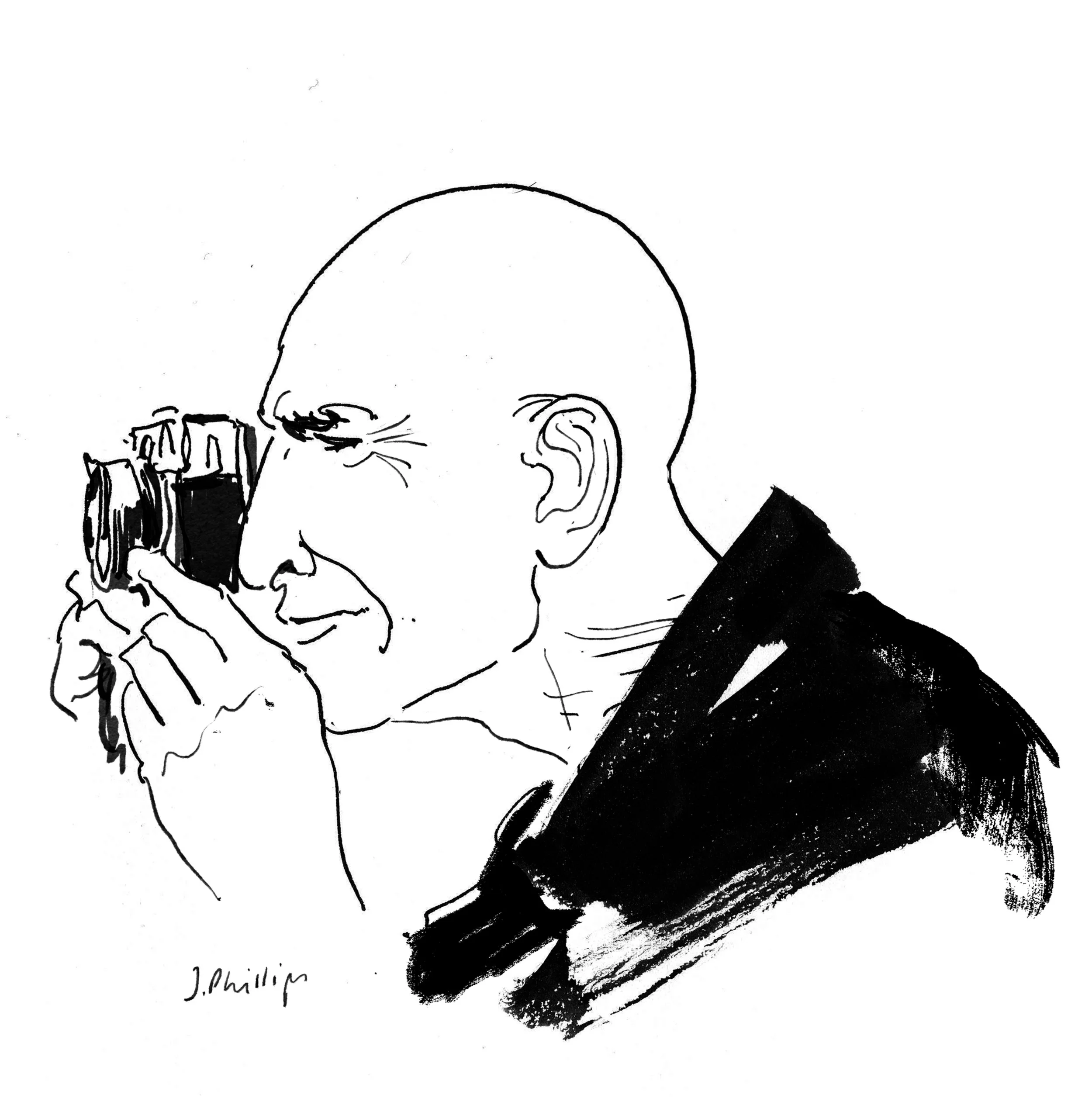

Adam Goldberg, Photographer

Adam Goldberg is a photographer, actor, director, producer, and musician. Perhaps best known for his roles in film and television, Goldberg has appeared in Dazed and Confused, Saving Private Ryan, A Beautiful Mind, and Zodiac. His TV appearances include the shows Friends, Joey, Entourage, The Jim Gaffigan Show, The Unusuals, and his critically acclaimed role as hitman Mr. Numbers in the first season of Fargo.

A multi-faceted, talented artist with a long history of diverse projects, Adam also loves capturing the beauty in the mundane.

He shares five photo books that have influenced his work, talks about how he got into photography, and how it has enhanced both his career and personal life.

Chromes,

by William Eggleston

“I've always been intrigued by how Eggleston walks this line between documentary photography and art photography. I’m looking at one particular photograph right now through the windshield of a guy washing his windows and the 76 sign in the distance. The photo is bifurcated by that. That thing on your windshield, the sort of shade, gradation of your windshield— it's just so remarkable. It's so stunning. It's essentially a snapshot. My focus is on the mundane, or that the mundane is intimate. There's this feeling of it being spontaneous, but also being very painterly.”

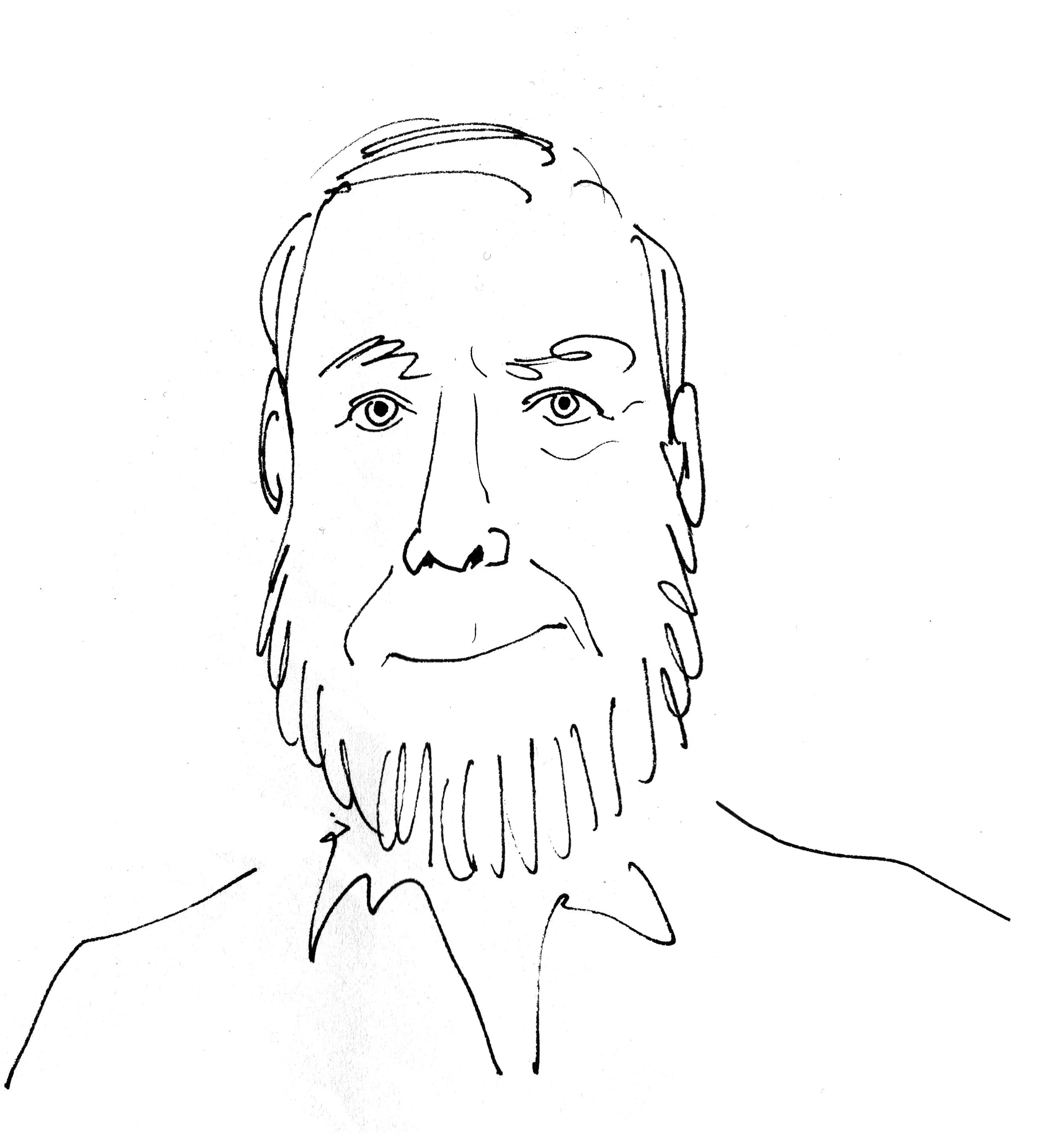

Emmet Gowin,

by Emmet Gowin

“He's got a long career, and he's known for these really intimate portraits of his family. It's a beautiful book, and there's a lot to read about him in the beginning. So much of his work is arguably this mundane stuff around the house, but it's fantastical looking. What he manages to do at home is so profound and so deeply moving. Some of it is very posed; some of it isn't. There's a lot of nudity. And it's extremely earthy. It's her and the earth, and babies and the earth, and her pregnant.

At the end of the day, there's just nothing that's much more effecting than seeing your family, and your wife, and your wife grown older, and your wife in these intimate moments. There's a picture of her peeing standing up, which is this brilliant shot. Her legs are a V. There are these great lines in the barn where she's peeing that are parallel to her legs. Shafts of light bursting through. It's really profound stuff. And again, it really walks that line between incredibly stylized and a snapshot.”

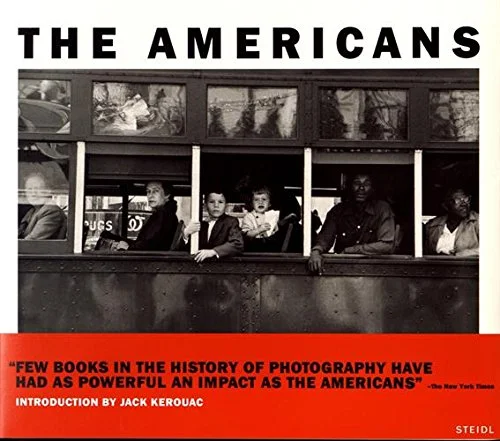

The Americans,

by Robert Frank

“There's two copies of it on my bookshelf. I brought one of them with me. He was doing those gas stations back then. There's this straight line through all of these people who have interested me—the beauty of the mundane. I love flipping through this book. I knew Robert Frank bizarrely as a filmmaker from Pull My Daisy, before I ever knew he was a photographer. In the 90s, Richard Linklater was passing out these videos, and he would make these compilation tapes. And he made one for me. It had a bunch of experimental films and Pull My Daisy was one of them. It had a big influence on the aesthetic of my film Scotch and Milk.”

Some Los Angeles Apartments,

by Ed Ruscha

“I've always been a huge Ed Ruscha fan and have been a fan of his 16mm films. It goes back to the thing that inspires me: the super mundane. He got me back into motion picture film, which I grew up making as a kid. This book is kind of an anthology. The original Los Angeles Apartments came out in the 60s maybe. And then this book is kind of about that book and also contains his book on gas stations.

So in some cases you'll see the picture of the thing which he was inspired by. There's a famous standard gas station painting, and you'll see the photograph that he took as the template for that as the study. Growing up in Los Angeles, this book also has apartments that I recognize, that's another reason that it's really neat to me.”

Adam, when did you start doing photography?

I did a series of photographs when I was 14 or 15. My family moved near Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles when that was still kind of cool in the 80s. It was odd because there was this dichotomy between all of these punk shops that opened up, like Poser, and vintage shops like Flip—these famous 80s Melrose iconic places. But then there were all these retirement hotels as well, which over the years have been turned into hipster hotels.

I did four photographs, and two were of neon signs. One was Wacko, this kind of famous store, and the other was this store called Hollywood Neon. The other two were of retirement hotels. I was really into this, the art of the street or whatever, the art of architectural photography, but with some kind of philosophical bent about how these two things were coexisting.

I wasn't aware of Eggleston's work until much, much later. I kinda want to say that yeah, maybe Eggleston got me into how I could use film to get a similar quality, or use certain kinds of films. He inspired me to take pictures of gas stations, which I've literally been doing my entire life. I'm more amazed that this guy was doing it back then and doing it in such a vivid, contemporary way that was so clearly revolutionary at the time. I'm blown away by most of the images.

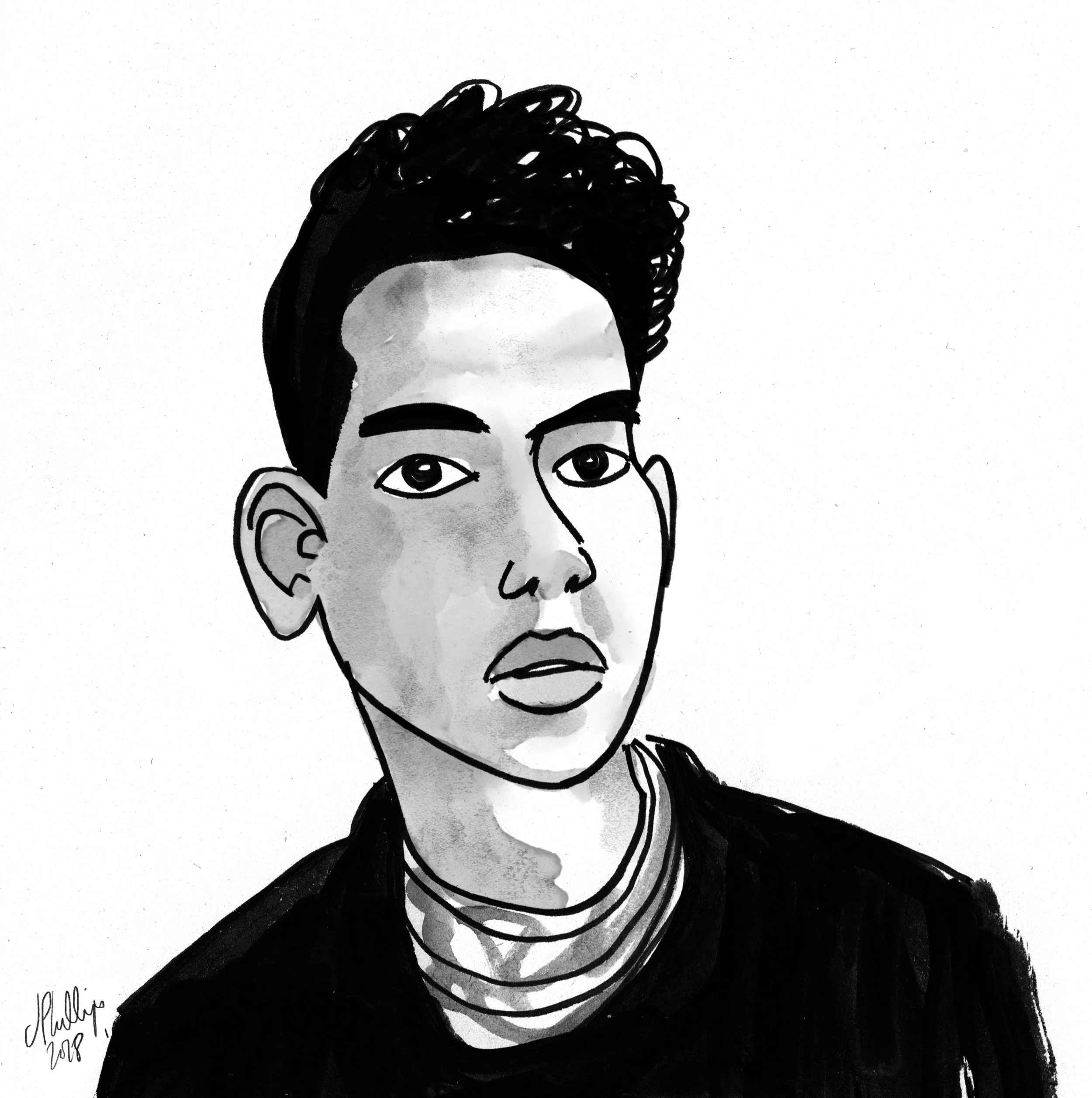

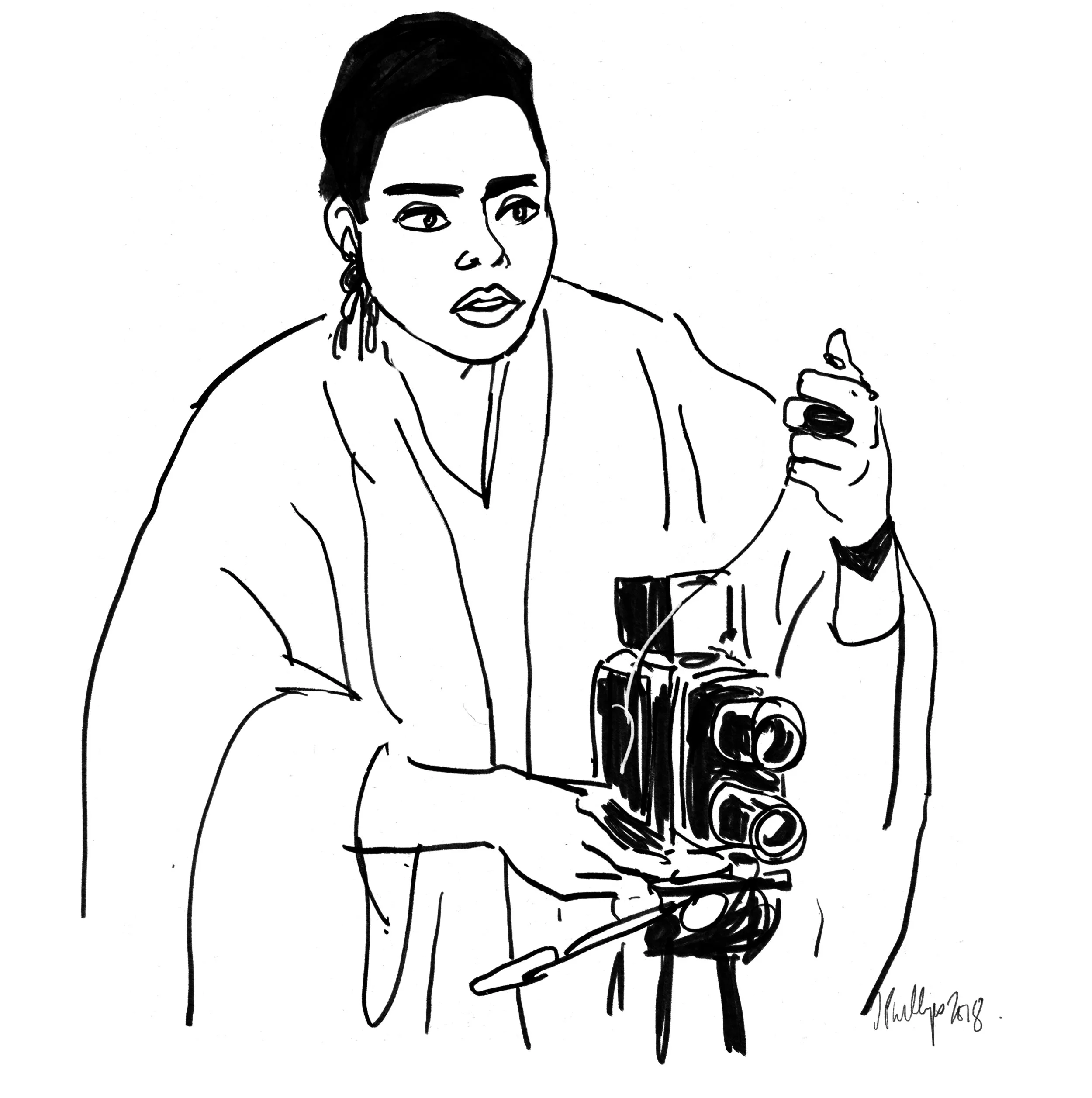

My wife Roxanne is the centerpiece of everything I've done since I've known her. She really inspired me to get back into photography. When I had met her, I had really not been that interested. I hadn't picked up my film cameras in a long time and was taking a lot of iPhone shots. But with my wife, I suddenly got back into instant photography and then really heavily into medium and large format film, as well as picking up my own 35mm. It's obvious that if I were to do any retrospective of the last decade, that it would essentially be about Roxanne.

The images that I use are often multi-exposures, several images on top of each other. I'm moved by the photographers that manage to convey in a single image what it seems to take me double exposures and triple exposures and quadruple exposures to say what I'm trying to say.

Do you think that your use of double exposure or multi-exposures is directly related to the fact that you've done so much in the world of cinema?

Oh, I'm pretty positive of that. I was intrigued by it but much more so after. I didn't take a double exposure of any kind until I had a Polaroid Pro Pack. It was like a cheap 3x4 peel apart camera. It wasn't cheap to buy. It was all that they made at the time and it was before I was buying vintage gear. So it was like at the end of the 90s.

I started taking all these multi-exposures then of my then-girlfriend Julie, which were pretty cool, usually a background of some sort. But that was after I had made this movie Scotch and Milk. It was heavily influenced by film noire, and hby multi-exposure sequences in old films.

I'm frankly kind of annoyed how common place it is. And I'm annoyed with myself for that matter. I'm no less annoyed with myself than I am at everybody else about it. That's probably also the nature of social media, where you start to realize that everybody's doing exactly what you've been doing. Although arguably, I'm older than your average social media user, so I like to imagine that.

For instance, you look at the work online of I'm going to do blank all of a sudden. So there's a picture of the dude's wife driving in a car on a road trip in the 80s and those are the same exact photos I've been taking of my wife from the 2000s. This begs a much larger discussion about whether there are any new ideas, which I don't think there are.

How do you find that being predominately known to the greater world for film-making influences the way you play with photography?

It kind of hits close to home in a way. It is always a weird feeling to be known for something that isn't the thing that you're most passionate about, and more likely the thing that you're not even best at.

First, you have to consider that there was no audience prior to social media, because what I have done publicly as a visual artist or as a musician had to be distributed through more conventional means, which were far more difficult. More people have seen my Instagram account that have seen my first film, Scotch and Milk, or heard any of the records I made. It's weird because I used to do all of these things prior to social media, like making short films. I was a teenager taking pictures in my early 20s. I guess my feeling was, well, I'm priming myself essentially to be a filmmaker. These are all things that involve making movies, and when I make movies, they will be exhibited and they will be seen, and eventually it will eclipse my work as an actor and I can then be just a filmmaker.

Well, that didn't really work out, partly because of the actual content of the movie I made, and partly because of how difficult it is to have people see your work. I was sort of struggling with this for a long time. Then social media comes around and somebody takes their shirt off and they have a million followers, right?

That hasn’t helped us yet personally.

Right. Well, I did have this weird brush with social media stardom when I was fucking around with Vine. And the irony of that was in the first month of using Vine. I was making six second versions of the weird shit that I'd been making for no one in particular for years and years on video when I was a kid, and arguably with the music I had been making and began distributing in 2009.

It's an interesting year because I did the show last year called Taken, and I kind of knew it wasn't going to go anywhere. But we all moved to Toronto for six months. I knew it would be enough to give me a year if something great didn't come along—it wouldn't be the end of the world. I had been focusing on this photography book/vinyl project called The Goldberg Sisters. I told myself I'm gonna really dedicate myself to that in a way that it doesn't feel like it's just some subsidiary of what I do.

And that's been both, much in the same way that I've taken time off to make movies. It's very fulfilling, but it's also this incredibly lonely vacuous experience as well. It's not a coincidence that I ended up acting to make my living. I always wanted a lot of attention and I was basically doing performance of some variety since I was six years old to anyone who would pay any attention. To make art in a vacuum was certainly never my intention. But I also know there is a physiological need, if you want to call it that, to capture things as they're occurring and to be removed from them and pursue them through the lens of a camera, whether literally or figuratively.

It kind of goes back to Vivian Maier. Here's this woman, completely ill-equipped to be taking care of children, and clearly is much more comfortable behind the lens of the camera. It's like, here I am, I have this job that requires me not just to perform but to interact with a lot of people during the course of a work day. Meanwhile, I have felt at my most comfortable either writing or editing, or quietly snapping a bougainvillea outside of my house.

So you do look at acting and photography both supporting one another, and using it to address the extroversion and introversion side of your personality?

Yeah, totally, that's a great way of putting it. I like using Instagram because ultimately it's such a mundane platform, so it sounds funny to say that you could learn more about me from my Instagram than my other work. You could say this about everybody because people are so confessional. You would learn more from what I have shared artistically about my inner life than you would from an episode of Friends or something like that—something for which I'm obviously more known.

The same with my music. This is all of the stuff that happens in the night, whether it does or it doesn't. It's how I feel at night. It's a sort of metaphor, I guess. In that regard, there's a real dichotomy that inhabits my pride and my struggle.

This is a much more literal response to the question, but I used to never take photographs on a set because I was way into acting. During Dazed and Confused, I remember Anthony Rap had a camera on before every shot, every take, he was taking pictures. And it really took me out of the moment. I was way into method acting and all this type of stuff. This is all kind of ironic because I was playing a thinly veiled version of myself. Still, that's not easy to do, even though people might think it is.

Same with Saving Private Ryan. Jeremy Davies gave me some photos I think he took on a Holga, and it's me and Edward Burns lying down between takes. I took pictures during Saving Private Ryan, but it was always after and before or from my trailer. There was never a camera on me. Looking back, it probably would've been nice. But I was the guy. It was really important that I was the guy.

Now, I'm not interested in taking backstage pictures of people. And I'm really not inspired by being on a set or a sound stage. Often times, the people I work with are quite interesting—obviously. I'll try and get them in a way that feels like we're not on set. I think one of my favorite photos is actually this double exposure of Jim Gaffigan at Katz’s Deli. It's a wild looking photograph.

When I really get inspired is when I walk back to the trailer. I have so many photos of me losing my mind in the trailer and the things I see in the mirror and through the window of my trailer in New York City and that kind of stuff. And that's the stuff that I'm actually thankful to acting for, because otherwise I really wouldn't leave the house.

You're also doing that more now? Before you were focused on the acting. Or not too focused, but more focused on the acting element of it.

Yeah. Often times, when I'm working I get a little depressed because it doesn't feel like I'm in my element. The camera is like a very large pendant around my neck that reminds me who I am.

What are some habits that keep you going? Maybe there's specific ones that apply to your photography, or maybe it's across the board.

I have a lot of them. Actually, since Saving Private Ryan, I've written in a journal, a variety of journals somewhere. Some had a lot of Polaroids. In fact, in the late 90s, I started writing in these big sketch books and I would try to put a Polaroid a day in there. And this lasted for some time. Sometimes it would be a Polaroid, sometimes it would be the bandage that was used to address a tattoo I got.

I have these books everywhere. But at a certain point that became too arduous, just insane. And I just kept a normal, much more mundane journal. Recently, in the last several months, I've stopped doing that everyday. I keep a digital. It's supposed to be a gratitude journal app, but really I use it to just keep track of shit.

I meditate. I try and do yoga, but I don't always. When I first got on Tumblr in 2010, I uploaded a photograph everyday for a year straight, which was generally an instant film that was scanned, because otherwise I couldn't upload one a day unless I was developing it myself.

That practice absolutely affected both my song writing and my picture taking. There's no way to separate the two because I became much more prolific in both regards. I don't do that anymore, but for awhile this Tumblr blog was an incredibly active place for me to express myself visually and aurally. I was like that with Instagram too, where I was like I’ve got to get the photo of the day. But it would generally be a photo from scanned images of analog film. It wouldn't be a photo I took that day necessarily. But that's fallen by the wayside.

Also, I'm in a weird place now with kids. We just had a baby some weeks ago and our older son started pre-school. I've barely been doing anything. It's literally about survival. Taking my kid to preschool and picking him up, and passing out.

What is something that you used to believe about photography that you had to change your mind about?

Photography has changed so much in terms of how it's made, and in terms of how it's distributed and exhibited and all that. I feel like what everyone once thought it was, it wasn't. I guess arguably like many things, like music and film and acting, and kind of almost like every artistic modality, I thought it was something that was more elite than it really is.

I believe two things. I believe the democratization of art is both good and bad. I think it crowds the market place. I don't mean literally, although it does that as well. The obvious example is if you go onto Netflix, the joke is everybody loves Netflix, but nobody knows what to watch. And so never has that been more true about every medium. Things aren't curated the way that they used to be. You went to a record store and you see, oh, the guys that work here really love this record, and chances are you fucking loved it too. That was how it worked.

I super miss that, both as a practical, as someone who's a consumer of that stuff, and as someone who wanted to be appreciated as an artist by those people.

On the other hand, you're exposed to so much sharing of photography, so much visual information. And while it can really cloud your plate, and it's tough to figure out what your diet of imagery is going to be because it really isn't curated for you; it has also had a great influence on me. With my friend Ben, I would not have been exposed to his work were it not for social media. And we clearly overlap in influences, in much of the same way that these actors I used to hang out with all the time and get drunk with and spend my days with. You can see if you look at certain movies, you can literally see one of us doing an impression of the other person. It's kind of painfully obvious.

There's incredibly important things about the process of using manual photographic tools that do elevate one's work, though I don't necessarily think it's necessary to make a good image.